Part 2

Bruno Fernandes was among those who wanted change by the end of Solskjaer’s reign (Photo: Paul Ellis/AFP via Getty Images)

Some who know the club allege there is an atmosphere of compliance among the hierarchy, into which Solskjaer fitted.

He challenged the decision-makers on many facets of the operation at Carrington but largely kept a diplomatic outlook on matters, whereas predecessor Jose Mourinho pressed the detonator button.

Solskjaer was open to United’s media team capturing footage at Carrington for use on social media, for instance.

Mourinho was different and his tenure left scars when it came to considering Antonio Conte’s interest in the job.

Conte, a serial title winner who was available following last month’s Liverpool humbling after leaving Inter Milan at the end of last season, was judged too volatile. Whether United now regret their decision to overlook the one out-of-work manager with a track record of triumph in England would be interesting to ascertain. Conte is now back in football with Tottenham.

Those wielding the power at United are said to have an inauthentic grasp of football, with some fellow executives taken aback by a lack of knowledge.

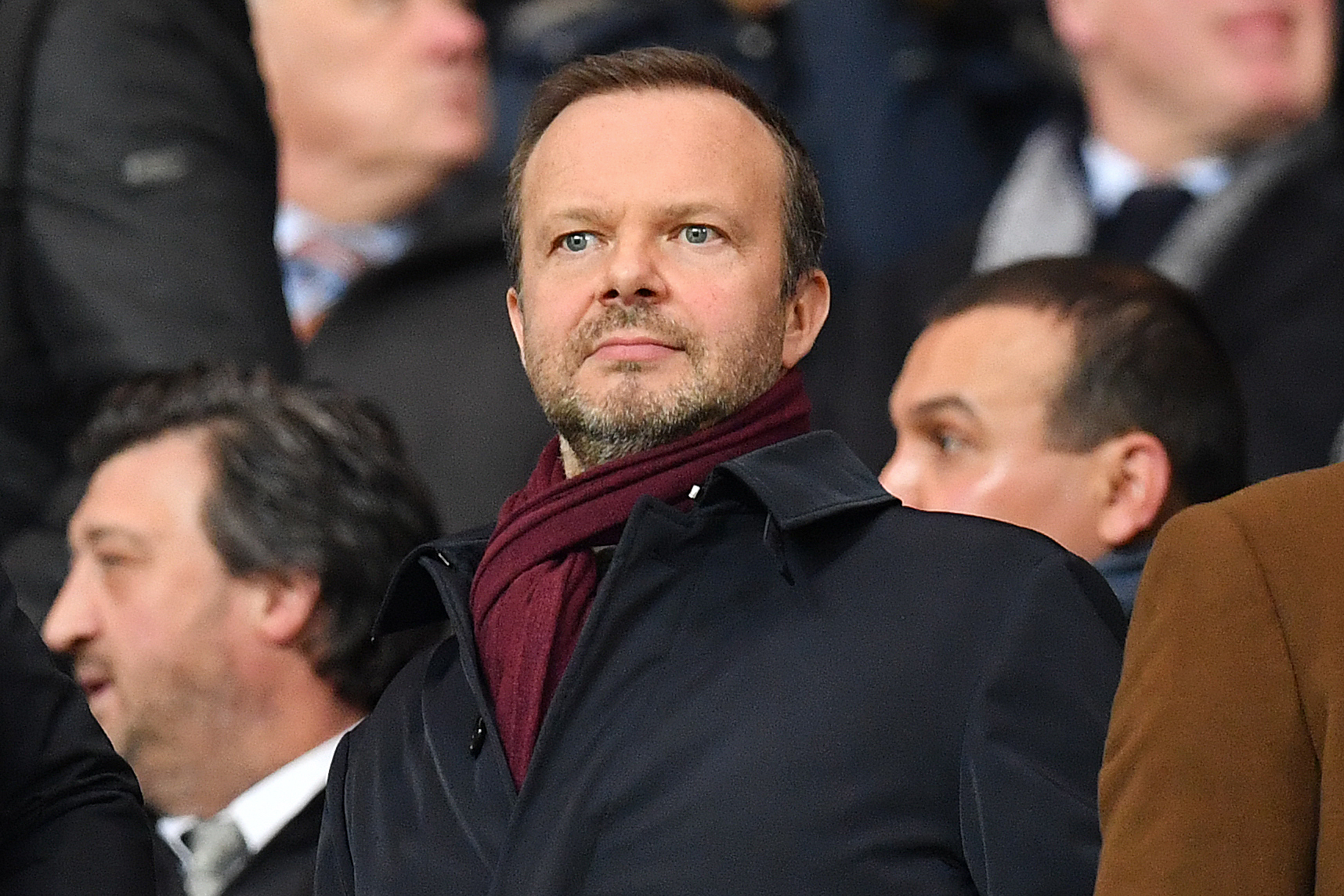

United’s contingent in the directors’ box at Vicarage Road on Saturday was described as looking “despondent” at the final whistle. Among those present were Judge, Murtough, non-executive director Mike Edelson, club secretary Rebecca Britain and John Alexander, who left his position as club secretary in 2017 yet, for reasons unclear, retains a consultancy role. Woodward is in line for a similar position once his resignation is realised, perpetuating the picture of cosiness at the top of the club.

Solskjaer surviving as long as he did is another strand to that accusation.

It is said Joel Glazer and Woodward, having bet big on the Norwegian, wanted to get away from continuing to hire and fire every two years in the post-Alex Ferguson era. But there is also a sense Woodward did not want to dismiss Solskjaer, a club legend from his playing days, as his last act. Likewise, Arnold, the expected new chief executive, was reluctant to do it as his first. United were desperate to get through to the end of the season and reassess things then.

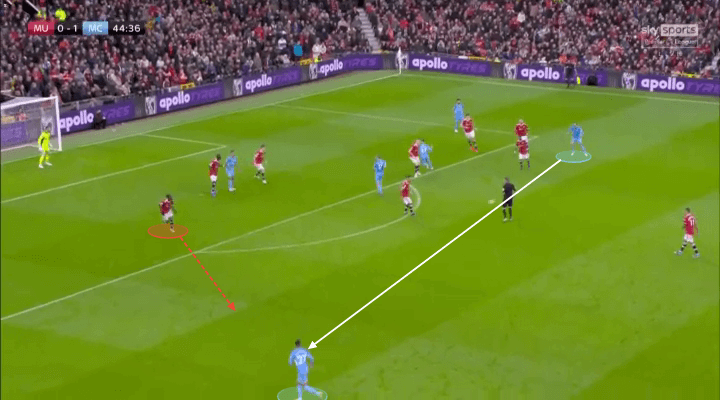

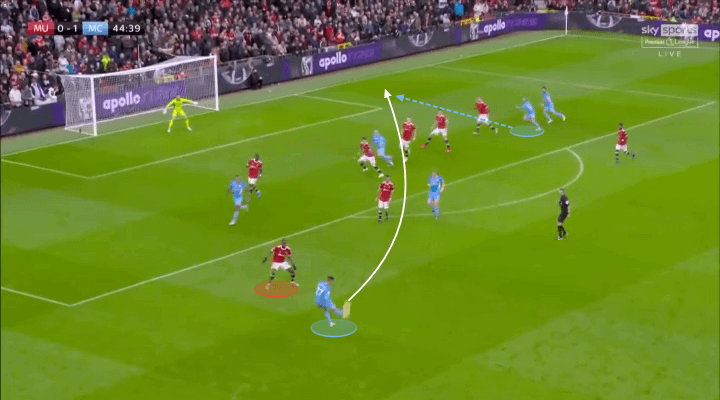

Woodward was also said to be “obsessed” with recreating the patience then-chairman Martin Edwards showed Ferguson when he was struggling in the early years of what became his glittering reign. That is why United did not dismiss Solskjaer at the start of this month’s international break after another painful loss that saw them outclassed at home by Manchester neighbours City, despite the gap of games providing space for change.

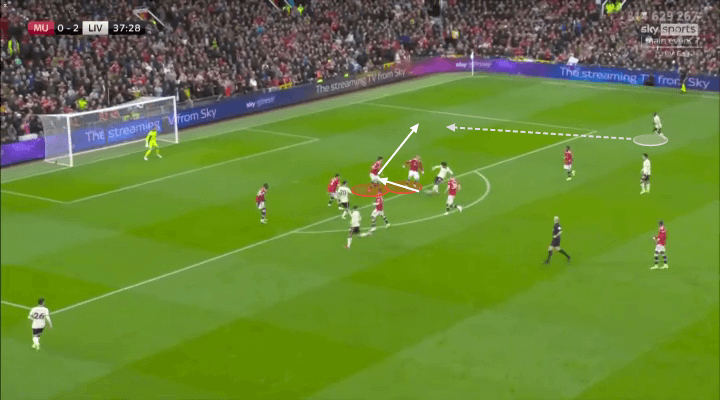

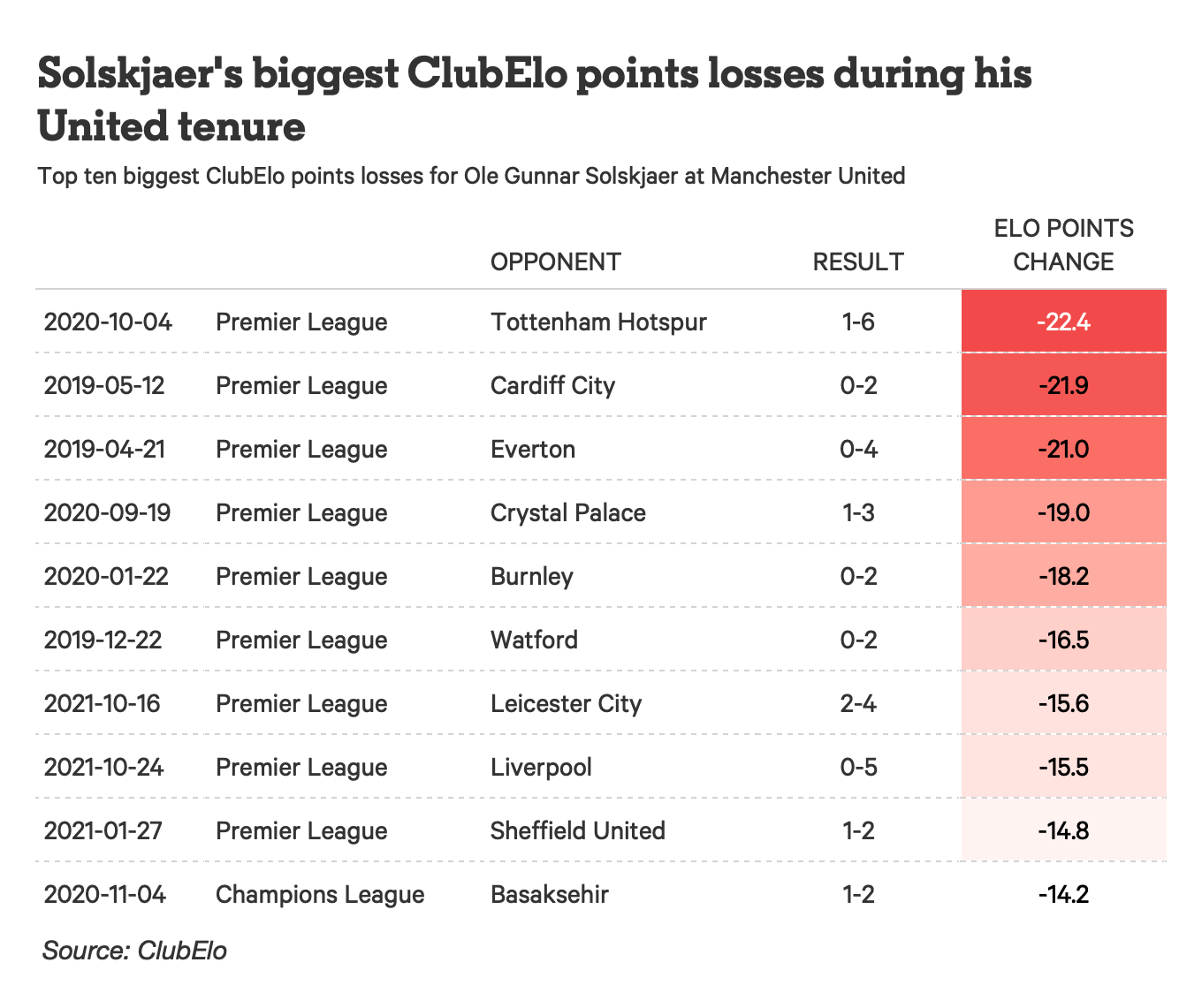

As late as Saturday night, hours after the Watford game ended, several sources insisted United had “no plan”. That absence of foresight blinded them to a situation that had, in reality, become extremely brittle after the 4-2 defeat away to

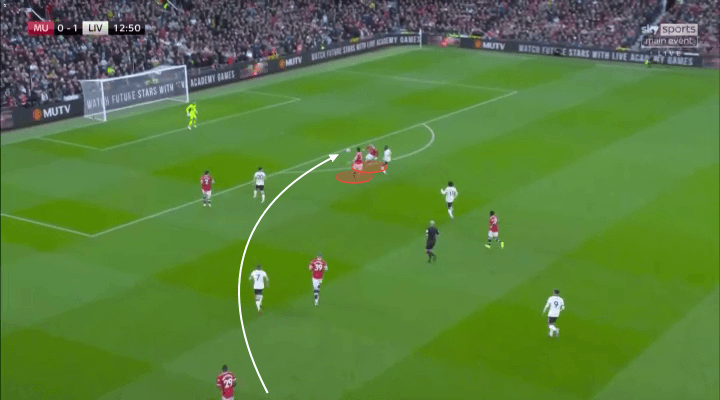

Leicester City last month and untenable following the Liverpool loss a week later.

The day after that 5-0 defeat at Old Trafford, one Premier League manager “eviscerated” Solskjaer in his own club’s canteen. He made it clear he thought Solskjaer was “out of his depth” and that United were one of the easier opponents to prepare for because they would come “without a coherent plan”.

This view was backed up by

Manchester City midfielder

Kevin De Bruyne, who told media in his native Belgium: “The day before a game, we usually train tactically, based on how the opponent play. Before United, Pep (Guardiola) said, ‘We don’t know how they’re going to play. We shall see’. And we stopped training after 10 minutes.”

United players were openly telling their representatives it was “the end of a cycle”.

On Saturday night, a source close to the squad said in response to Solskjaer’s chances of survival: “How many times do we need to ask the same question? It’s been obvious to all of us – and the players say the same – for weeks.”

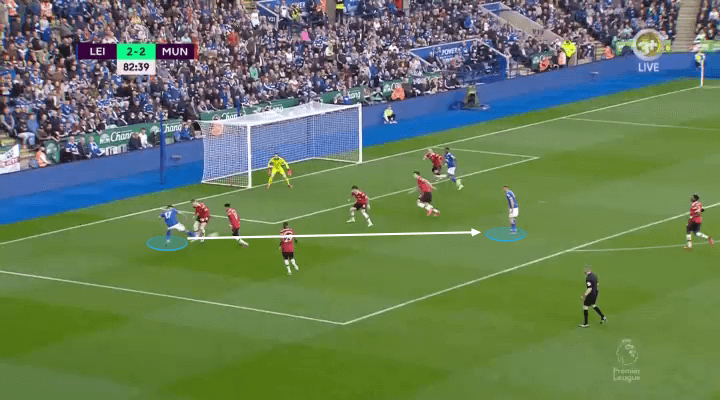

For some close to the team, Solskjaer’s reign had become a “circus” by the time United were limping away from the King Power Stadium on October 16.

In the dressing room following that chaotic defeat, where United got it back to 2-2 on 82 minutes only to promptly concede again before their hosts added a late fourth, Solskjaer asked his players: “What’s the problem?”. Their silence in response told a story.

Eventually,

Eric Bailly stood up and questioned why fellow centre-back

Harry Maguire, with one training session under his belt after missing three weeks with a calf strain, had been picked to play rather than him.

The Leicester defeat saw recriminations in the dressing room (Photo: Matthew Peters/Manchester United via Getty Images)

Solskjaer is said to have become defensive, insisting that, as manager, he made the decisions. This caused confusion, given his initial request for feedback. When the manager left the room, Fernandes spoke at length, encouraging his team-mates. Eventually, a couple of them suggested any pretence should end and the real issue addressed. A very senior player is said to have quietly replied to that: “We all know what the problem is.”

While never becoming openly mutinous, a silent lack of belief in Solskjaer spread among the squad from that point, diminishing his authority. Bailly’s protest also speaks to a criticism of Solskjaer’s treatment of players. He has deftly handled

Mason Greenwood’s development, offering patience when the young forward lost focus, but there are some on the fringes who feel misled.

“Ole is a nice guy, everyone knows that,” says a source close to the players. “But he’s not a good man-manager. People think the two are the same but they’re not.”

Going back two years to his first summer in charge, Chris Smalling was forced into a sudden change of plans when told by Solskjaer on the final day of the summer transfer window he would be going to Roma on loan.

This summer, Solskjaer kept

Jesse Lingard, who shone on loan to

West Ham United after joining on loan in January, then gave him 64 minutes of Premier League football across the first 12 games. Bailly signed a new contract to 2024 in April but has played only three times this season, just once in the league.

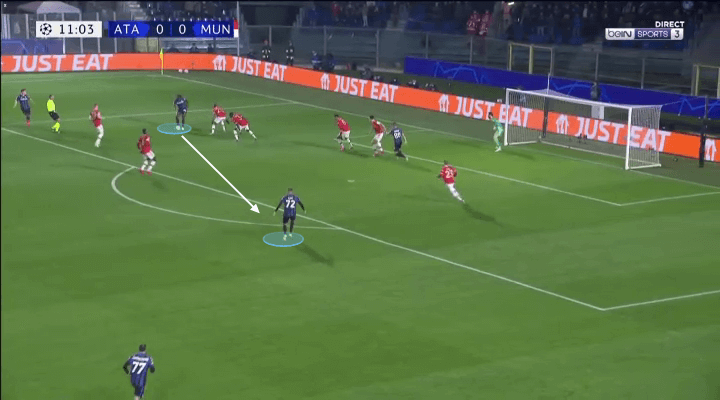

Young winger Amad has accumulated 264 minutes in eight appearances across all competitions since joining in January from Atalanta in a deal worth £37 million. A mooted loan to Dutch club Feyenoord broke down when the 19-year-old sustained an injury but he is said to be wondering about his involvement now he is fit and far too good for under-23 level.

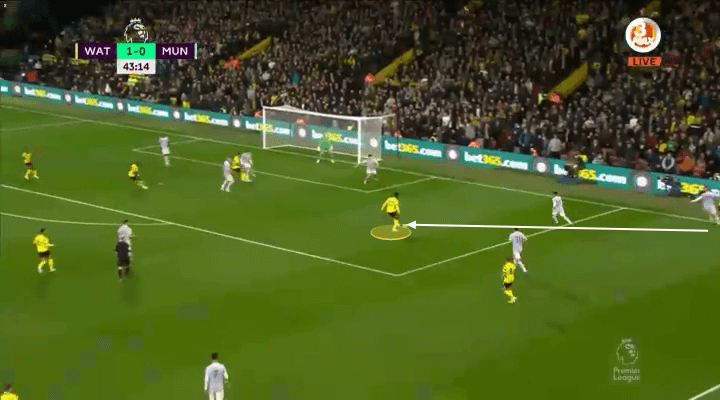

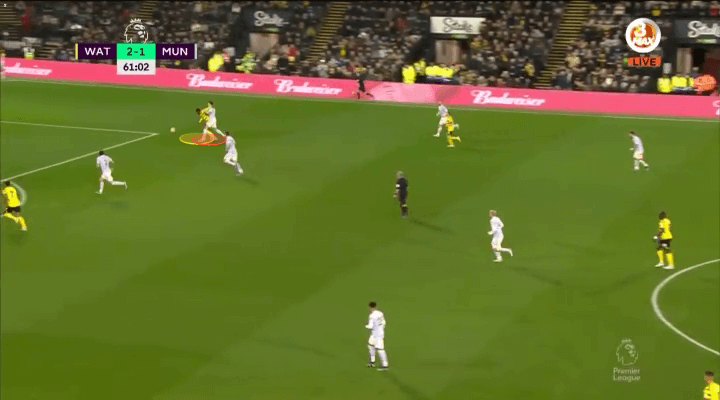

Donny van de Beek’s case for inclusion is well-documented and his superb display off the bench at Watford as Solskjaer’s final throw of the dice painted the manager’s reluctance to use him in an even more curious light. Van de Beek was told in the summer he would get more chances but he had 15 minutes in the Premier League this season prior to Saturday. It is said Solskjaer was angrier than he showed over disparaging comments regarding the situation made at the start of last season by Van de Beek’s mentor.

Daniel James, a summer departure to

Leeds United, was told by Solskjaer that he remained part of his plans following the arrival of Ronaldo in late August and started two days later in a 1-0 victory at

Wolves. Soon after the final whistle, it was made clear by a different club representative that James would now be

eighth choice in his position and needed to make the £25 million transfer to Elland Road.

Typically, United have been poor at selling their fringe players, leaving some to remain in the squad but feeling disenfranchised and undermining the mood. Still, there are people close to Solskjaer who feel that there should have been greater rotation.

Alex Telles has been pushing unsuccessfully to rival

Luke Shaw for game time while

Diogo Dalot is surprised he has not dislodged

Aaron Wan-Bissaka, who is the only United outfield player to have played every minute of the Premier League season so far.

“Ole has his favourites,” says another source.

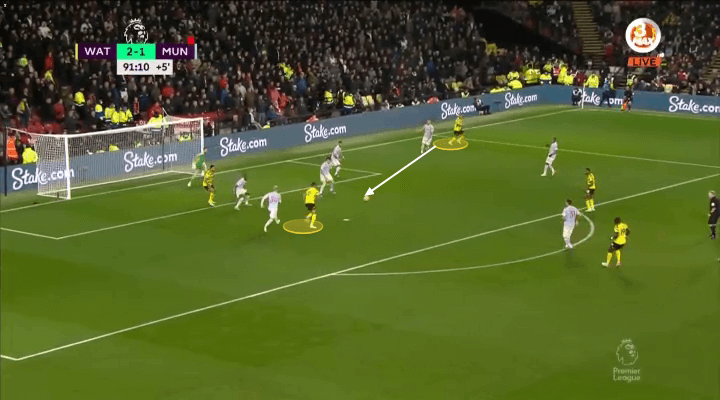

Seven players started all four of the calamitous defeats to Leicester, Liverpool, City and finally Watford.

Solskjaer’s intransigence is seen as faith to those who have performed for him previously but it has also been interpreted as a lighter touch to avoid conflict.

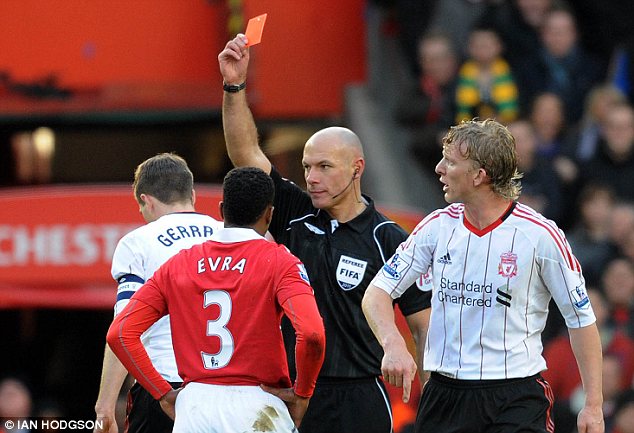

A naturally sunny disposition could be seen even as the darkness descended at Vicarage Road.

He gave a low five to Maguire as he walked off the pitch following a dismissal for two unnecessary bookings that cut United’s comeback dead. Solskjaer also ruffled the hair of Watford’s

Tom Cleverley, a former United player he worked with as the club’s reserves manager over a decade ago, when passing behind him down the touchline to carry out his post-game broadcast interviews.

Solskjaer let Claudio Ranieri encroach into his technical area without comment as the Watford manager wildly gesticulated to his players. He apologised for smiling in his Sky Sports interview after the 4-1 defeat.

Where once his upbeat energy lifted the Mourinho gloom, it began to come across to players as a lack of edge or ruthlessness.

Sources close to Solskjaer actually grew worried about him towards the end, with the relentless positivity appearing to be a front.

There is similar sentiment around his coaching set-up.

McKenna is regarded as an excellent coach but, according to sources, was given “too much responsibility” by Solskjaer, considering his level of experience. McKenna is 35 and was promoted from the under-18 side during Mourinho’s tenure, with Woodward advocating his progression to bring on a young team.

Solskjaer was happy to oblige but there is a feeling the players aren’t buying into the instructions McKenna gives when he leads sessions. Carrick has the playing pedigree and is an astute mind, but generally quiet. A source says: “The coaches are doing the work, good sessions, then it all falls to pot on game day. That’s clearly a concern. Are the players taking it on board?”

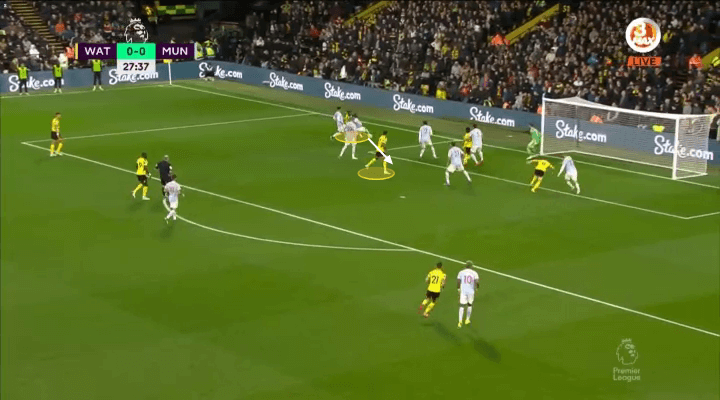

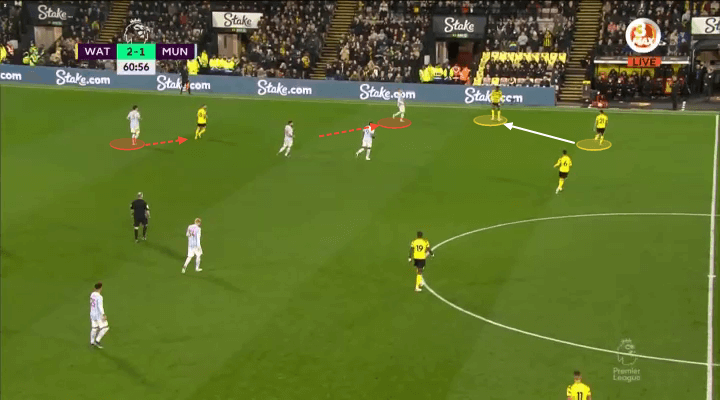

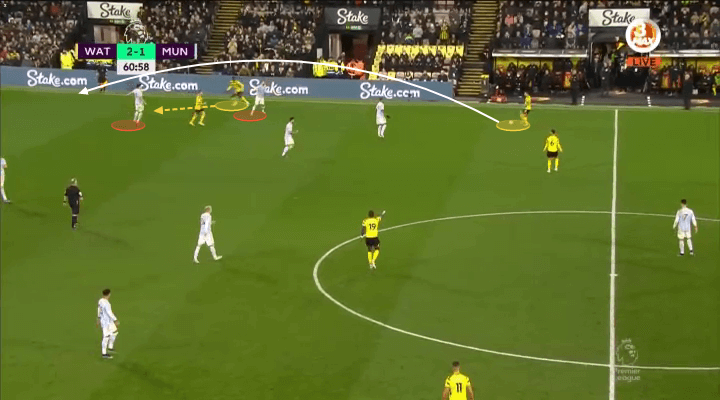

There was a moment midway through the first half against Watford that illustrated the confusion.

Ronaldo, Fernandes and

Marcus Rashford were all over to the left side of the pitch, with

Jadon Sancho isolated on the right. Solskjaer waved frantically to try to get the team balanced. McKenna slapped his hands by his side in frustration. Solskjaer ushered his assistant to sit down while he continued to direct the players’ movement.

Rashford then being taken off at half-time for

Anthony Martial caused a jolt in the dressing room.

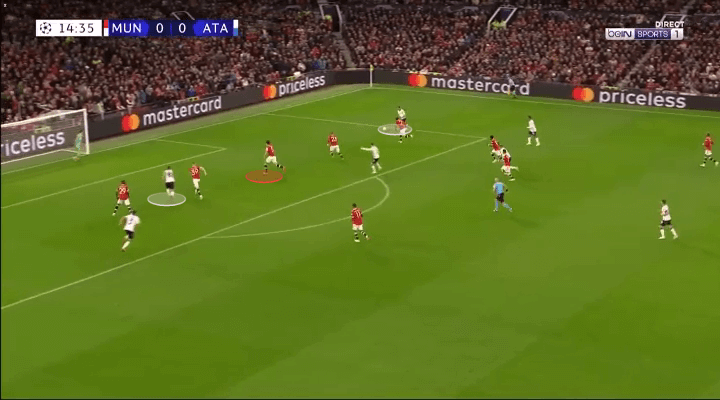

Donny van de Beek was used only sparingly by Solskjaer despite costing United £35 million (Photo: Matthew Ashton – AMA/Getty Images)

Some think Phelan, 59, could be used to a greater degree, in the way Pep Guardiola has leant on 56-year-old Juanma Lillo across town at City. Phelan’s role is sometimes unclear to players at Carrington but his great experience is visible on Champions League nights, when he is the one to stand in the technical area.

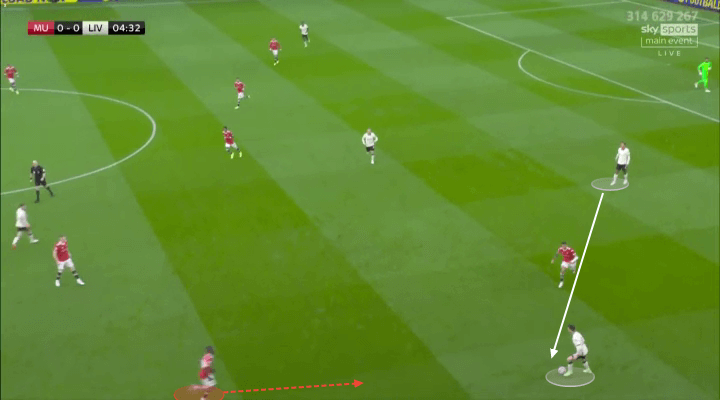

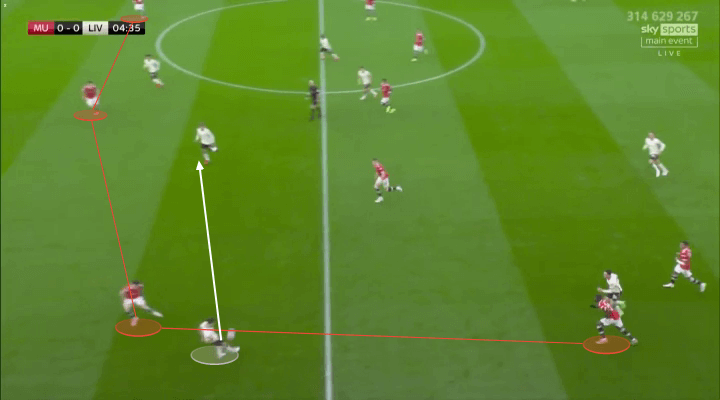

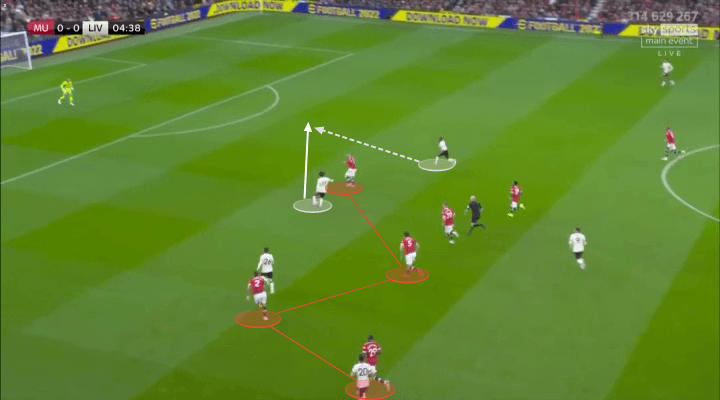

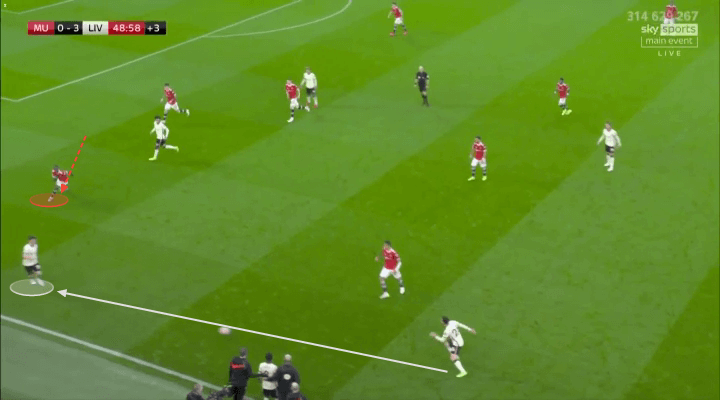

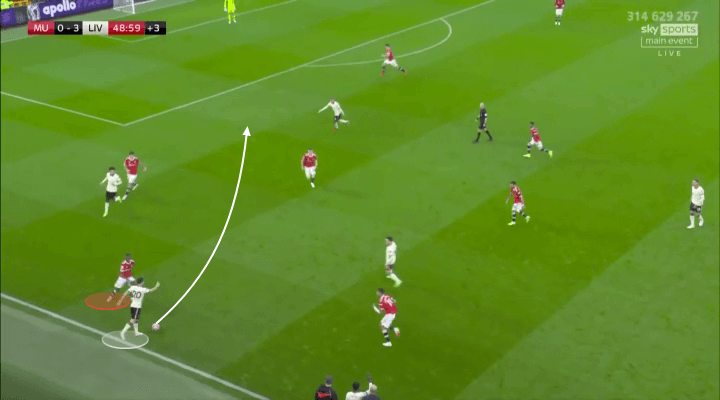

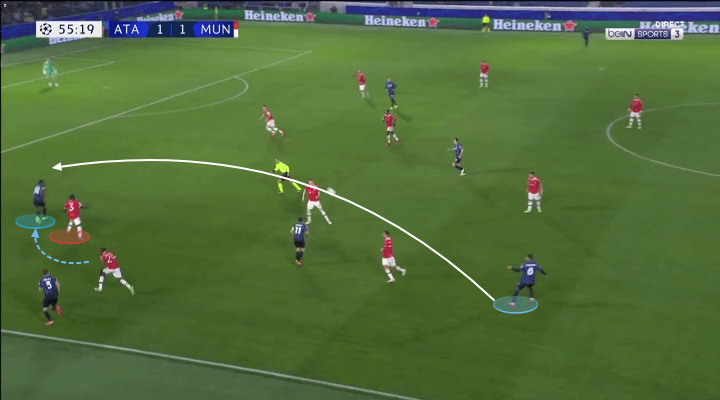

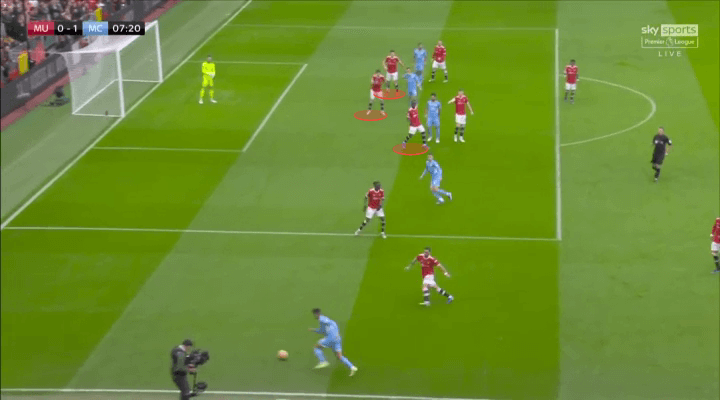

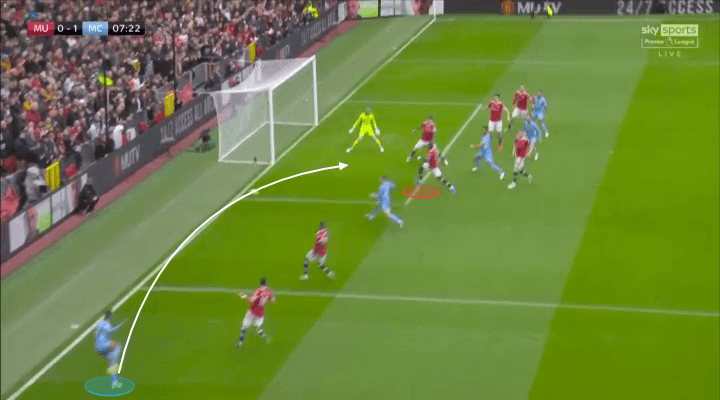

No amount of instruction from the side could rescue the desperate display against Liverpool, which was doomed to fail when players were left uncertain over Solskjaer’s strategy to press their visitors. The 2-0 home loss to City two weeks later was even more dispiriting for its subservience but one rival player was struck by Solskjaer’s pleasant mood in the tunnel afterwards. “He did not look like someone on the brink,” a source says.

Solskjaer, at that stage, was still solid in his position, to the point of giving his squad a week off during the international break. He recharged batteries himself back in Norway with his wife and children, surprising some players given the circumstances.

His human touch has been beneficial in the revitalisation of Shaw and

Edinson Cavani’s decision to stay for another season after signing a short-term contract only for 2020-21 and, whatever the strain of managing, he remains a family man. There have been occasions when he has done the school run in Cheshire before training — or after going in early — with sessions prepared the day before.

That work-life balance has perhaps helped him stay bright in pre-match press conferences.

Before the Watford game, Solskjaer said: “We’ve made sure that we’ve prioritised a couple of things that we needed to improve the most. We can’t concede easy chances against any team. I’m sure we’ll see a good reaction.”

The optimism was misplaced as United produced maybe their most calamitous display of the campaign.

Ronaldo recognised the players needed to take responsibility last week. He gave a speech calling for effort and application to be increased, whatever anyone’s concerns over Solskjaer.

That his words went unheeded by some at Vicarage Road triggered a furious reaction. He stormed down the tunnel, first off the pitch at the final whistle. Portugal team-mates knew that look from the European Championship this summer, where he privately seethed at performances as the title they won in 2016 slipped away. More recently, he cut an annoyed figure with coach Fernando Santos last Sunday after a 2-1 home defeat by main group rivals Serbia threw their qualification for next year’s World Cup finals into the jeopardy of the play-offs in March.

But a source says: “Ronaldo is different to how he’s portrayed. In training, he is respectful, listens to every session, is a top pro, gets his head down, does the work.” He has a particular affinity with Darren Fletcher, who gave him detailed instruction on the sidelines at the weekend while Watford’s

Ismaila Sarr was down getting treatment.

Fletcher has become a noticeable presence on match days, assisting with the warm-ups and moving to the dugout, having begun his job as technical director sitting in the stands. His additional work on the training pitches, unusual for someone with his job title, is said to reflect a lack of direction over his exact working brief, so he is helping where he can. Sources say greater definition is required.

Ronaldo has been a lightning-rod for debate about United’s issues but the view from the staff is that he very clearly raises the team’s levels. They gauge that his economy of movement only takes United’s running stats down by a few percentage points and team-mates should squeeze out that little bit extra to compensate given his elite potency in front of goal — as in his first spell at Old Trafford. Coaches have worked on this in sessions, seeing synchronicity, and struggle to reconcile what then happens on the pitch during the games.

One player who could never be charged with insufficient sprinting is Fernandes but his solo pressing has caused frustration. Coaches have gone through his videos with him to highlight the wasted energy. They have also grappled with Maguire’s form. Made captain by Solskjaer, there are some who feel the England centre-back is struggling with the pressure that comes with the armband.

Eyebrows have also been raised at how little went into preparing summer signing Sancho for a new challenge. The 21-year-old went from barely featuring for England at Euro 2020 and then a holiday, straight into the intensity of Premier League for the first time without a full pre-season or being brought up to speed over the summer,

not helped by a serious ear infection along the way.

Solskjaer would have wished that fellow summer addition

Raphael Varane was available to him more often. The World Cup-winning France defender has missed all four of the defeats that cost him his job, but played the full 90 minutes at Spurs, where his communication in a back three aided the keeping of a rare clean sheet. That 3-0 win was also Cavani’s last start under Solskjaer, and there is disappointment that the Uruguay striker, who last week underwent treatment on a knee tendon issue, was unable to present himself fit more frequently given his quality.

When Solskjaer praised Cavani for delivering the best training session he’d seen since being in charge it was, sources say, a coded message for others to match the 34-year-old’s effort. “Ole has been let down by some of the players,” insists one.

Insiders say there is a small divide between some of the older and younger players, which Solskjaer was attempting to bridge. That’s perhaps natural, given people tend to associate with those similar to themselves, but it is an aspect for the incoming manager to look at. Not everyone attended the team bonding meal at a restaurant in the Cheshire suburb of Hale at the start of November, although Rashford and

Paul Pogba were ill that day.

Establishing wider harmony was a key achievement of Solskjaer’s near three-year reign. A former colleague says: “He gave a huge amount of trust to backroom staff, sport science and recovery teams, listened to advice and implemented it, respected people’s specialities, compared to previous managers who either thought they knew best or ignored it.”

As Solskjaer left Carrington on Sunday afternoon, following four final hours at the complex, he was reminded of the link he strengthened with fans.

He stopped his black Range Rover and got out of the driver’s seat to hug one supporter who was waiting for a picture.

“It’s been an honour to work for Man United,” he told those nearby.