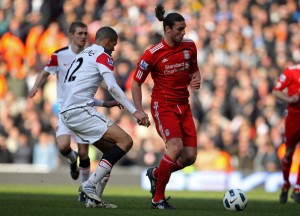

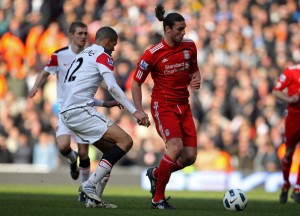

Finally, some six weeks after signing, Andy Carroll squeezed his considerable frame into a Liverpool shirt and entered the action from the bench. Against Manchester United his introduction appeared to change the game for the worse – although the game was effectively already won – but against Braga his slipped more seamlessly into the action.

Perhaps the biggest problems Carroll will have relate to his transfer fee, and the lingering memories of Torres at his best: two markers of high expectation. It’s fairly unlikely that he’ll reach such heights, but equally, having only just turned 22, he has youth on his side, not to mention hunger (something the Spaniard seemed to run out of, at Liverpool at least).

But rather than be the star of the show – “the £35m man†– Carroll merely need be a component. The role of target man is not necessarily to score lots of goals; bringing others into play can be more important. If you have goalscorers in other areas of the starting XI, a spearhead striker can create chances by holding the ball up, flicking it on, or simply by making a nuisance of himself.

In his first two seasons at Chelsea, Didier Drogba’s scoring ratio was mediocre, but he was the focal point for Lampard, Duff, Robben and others, and both times the Blues won the league.

The good news is that Carroll looks like a fine finisher, so he shouldn’t fall victim to the ire directed at Emile Heskey, who had a tendency to choke in front of goal. (And with Heskey, the problem was that, Owen aside, there just weren’t enough scorers in Houllier’s ‘anti-possession’ side – especially after 2001 – and the midfield rarely got beyond the strikers. Gary McAllister only scored one goal from open play for the Reds, and Danny Murphy also tended to notch from free-kicks and penalties.)

But any new striker with a big price tag will feel increased pressure, particularly when taken from the comfort zone of a club where he was eased gently into first team football, with little initial expectation. (I call this the Shaun Wright-Phillips Effect: sensational at Manchester City first time round, having developed steadily as a younger player, but a failure at Chelsea.)

Carroll’s presence is about making Liverpool a stronger unit, not wowing the fans in quite the same way that prime-years Torres did; I don’t expect our jaws to drop quite as often. Also, the crux of the deal is that Liverpool got two young strikers for little more than the price of a single older, injury-prone one.

Right now, based on the evidence of the first handful of matches the pair have played for their new clubs, I’d have happily swapped Torres for Suarez. Straight swap, with both valued at £20m, £35m or £50m.

The little Uruguayan has already done things worthy of Torres at his best, whereas at Chelsea, Torres continues to look like the moody, relatively mediocre player who’d failed to spark into full life for Liverpool for 18 months (although his goalscoring record under BenÃtez and, briefly, Dalglish, remained impressive).

My feeling is that, heading into the future, Suarez can do more for Liverpool than Torres would have. He’s got a long way to go to match the Spaniard’s output at his best, but he’s clearly far better technically, more tenacious and a harder worker. I’d expect him to score fewer goals than Torres – though I feel that he could easily make it to 20 in a full season – but he looks certain to create more.

If looked at like this, with Suarez = Torres, Carroll becomes a mere bonus.

Now, if he flops, we can argue that the £35m could have been better spent. But if Suarez continues as he has been – and indeed, he’s likely to improve as he gets used to the league and to his team-mates’ style and movement – the two-for-one deal will already have improved Liverpool in relation to a fading (or, at best, disinterested) Torres.

In a sense, paying £35m for Carroll has also taken the pressure off Suarez; had Suarez been the biggest buy, then more focus would be on him right now. As it stands, Carroll has to bear the brunt of the focus. (Also, being an England team ‘great hope’ adds to the demands put upon his broad shoulders by the media.)

Parallels

When they joined in 1987, it was John Barnes – at £900,000 – who wowed the fans, while Peter Beardsley – at a British record £1.9m – took a few months longer to find his feet in Dalglish’s reconfigured side. We absolutely revere Barnes, but at the time of signing he was seen as inconsistent and somewhat peripheral, while Beardsley had shone at the World Cup a year earlier.

As good as Beardsley eventually was, it makes more sense to swap their price tags in terms of how they eventually performed in a red shirt; Beardsley was very good indeed, while Barnes was phenomenal. The same may end up being true of Carroll and Suarez.

As with 1987, it also could be the departing superstar striker – in that instance, Ian Rush – who suffers. While the parallels are rife, it is of course a totally new situation, with different individuals.

Also, Torres may spring to life at Chelsea; it wouldn’t surprise me. But with every passing month in this kind of form, the sense that his best is behind him will become stronger. Add the British record price tag – something that didn’t weigh him down at Anfield – and the fact that he appears to be forcibly shoe-horned into a formation that doesn’t suit the team (and therefore him), and it becomes even harder for him to be the sensation we witnessed between 2007 and 2009.

(Of course, there’s a chance that Chelsea may end up being successful even if Torres never returns to his sharpest; if he plays a role in them winning major honours, they’ll have few complaints.)

Style

One of fans’ key dislikes is hoofing from the back. Carroll represents a fear, in that he’s presents an easy option for the less cultured centre-backs to boot the ball long. So there might be occasions when he’s sought out at the wrong time, where a pass to someone else might be more wise.

However, the flip side is that when defenders are forced to clear their lines, they now have someone who can turn a clearance made under pressure into almost a 50-50 chance to keep possession.

I say 50-50, as centre-backs have an easier task winning headers because, usually, there’s two of them to one striker, and they aren’t looking to do anything bar clear the ball the way they are facing; even if the forward wins the header, if he flicks the ball beyond the centre-backs the likelihood is that the keeper will sweep up.

So normally, a striker has a less than 50-50 chance of winning the header – he’s outnumbered – and if he does win it, the chance of retaining possession – because there are more defenders and also a keeper looking to pick up the second ball – makes it around 20-80 at best.

Where Carroll excels is that: a) he’s big and strong, b) he has a great leap, and c) the accuracy of his headers (and chested lay-offs) is exceptional. We saw against Braga that possession could be built higher up the pitch, by Carroll winning it in those areas, in a way that Kuyt couldn’t.

Of course, this is essentially what Roy Hodgson wanted: bypass midfield, and have two big men to hold the ball up, and then the midfield join in. The trouble was, he had us play this way even when we clearly lacked the personnel; and it should be an option in a game, not Plans A-Z. The Liverpool way is not to try to pass from the back, first and foremost.

A further problem was that Hodgson appeared to want two strikers, playing parallel. Only last week, Steve McLaren noted how hard it is to play with a flat 4-4-2 these days, with two out-and-out strikers.

Hodgson seemed to realise this at Fulham, with Zoltan Gera in the hole, but at Liverpool – despite the option of Gerrard – he often opted for the flat pairing of Ngog and Torres. (You could see Hodgson buying Carroll, but not Suarez. And Carroll without that kind of partner is not something I’d be happy to see.)

When he came on against United, Carroll looked slow and clunky, as befits a big lad who’s spent months on the sidelines. It could be a while before the pace (of which he has a decent amount) and power return. There were signs against Braga, but he’s not yet at the level seen earlier in the season.

The rest of this campaign should be about acclimatisation. Even if he offers absolutely nothing this season, it can serve as a bedding-in process; the like of which would possibly have affected next season, if he had been bought this summer. By the time August comes, he should feel part of the furniture.

Perhaps the biggest problems Carroll will have relate to his transfer fee, and the lingering memories of Torres at his best: two markers of high expectation. It’s fairly unlikely that he’ll reach such heights, but equally, having only just turned 22, he has youth on his side, not to mention hunger (something the Spaniard seemed to run out of, at Liverpool at least).

But rather than be the star of the show – “the £35m man†– Carroll merely need be a component. The role of target man is not necessarily to score lots of goals; bringing others into play can be more important. If you have goalscorers in other areas of the starting XI, a spearhead striker can create chances by holding the ball up, flicking it on, or simply by making a nuisance of himself.

In his first two seasons at Chelsea, Didier Drogba’s scoring ratio was mediocre, but he was the focal point for Lampard, Duff, Robben and others, and both times the Blues won the league.

The good news is that Carroll looks like a fine finisher, so he shouldn’t fall victim to the ire directed at Emile Heskey, who had a tendency to choke in front of goal. (And with Heskey, the problem was that, Owen aside, there just weren’t enough scorers in Houllier’s ‘anti-possession’ side – especially after 2001 – and the midfield rarely got beyond the strikers. Gary McAllister only scored one goal from open play for the Reds, and Danny Murphy also tended to notch from free-kicks and penalties.)

But any new striker with a big price tag will feel increased pressure, particularly when taken from the comfort zone of a club where he was eased gently into first team football, with little initial expectation. (I call this the Shaun Wright-Phillips Effect: sensational at Manchester City first time round, having developed steadily as a younger player, but a failure at Chelsea.)

Carroll’s presence is about making Liverpool a stronger unit, not wowing the fans in quite the same way that prime-years Torres did; I don’t expect our jaws to drop quite as often. Also, the crux of the deal is that Liverpool got two young strikers for little more than the price of a single older, injury-prone one.

Right now, based on the evidence of the first handful of matches the pair have played for their new clubs, I’d have happily swapped Torres for Suarez. Straight swap, with both valued at £20m, £35m or £50m.

The little Uruguayan has already done things worthy of Torres at his best, whereas at Chelsea, Torres continues to look like the moody, relatively mediocre player who’d failed to spark into full life for Liverpool for 18 months (although his goalscoring record under BenÃtez and, briefly, Dalglish, remained impressive).

My feeling is that, heading into the future, Suarez can do more for Liverpool than Torres would have. He’s got a long way to go to match the Spaniard’s output at his best, but he’s clearly far better technically, more tenacious and a harder worker. I’d expect him to score fewer goals than Torres – though I feel that he could easily make it to 20 in a full season – but he looks certain to create more.

If looked at like this, with Suarez = Torres, Carroll becomes a mere bonus.

Now, if he flops, we can argue that the £35m could have been better spent. But if Suarez continues as he has been – and indeed, he’s likely to improve as he gets used to the league and to his team-mates’ style and movement – the two-for-one deal will already have improved Liverpool in relation to a fading (or, at best, disinterested) Torres.

In a sense, paying £35m for Carroll has also taken the pressure off Suarez; had Suarez been the biggest buy, then more focus would be on him right now. As it stands, Carroll has to bear the brunt of the focus. (Also, being an England team ‘great hope’ adds to the demands put upon his broad shoulders by the media.)

Parallels

When they joined in 1987, it was John Barnes – at £900,000 – who wowed the fans, while Peter Beardsley – at a British record £1.9m – took a few months longer to find his feet in Dalglish’s reconfigured side. We absolutely revere Barnes, but at the time of signing he was seen as inconsistent and somewhat peripheral, while Beardsley had shone at the World Cup a year earlier.

As good as Beardsley eventually was, it makes more sense to swap their price tags in terms of how they eventually performed in a red shirt; Beardsley was very good indeed, while Barnes was phenomenal. The same may end up being true of Carroll and Suarez.

As with 1987, it also could be the departing superstar striker – in that instance, Ian Rush – who suffers. While the parallels are rife, it is of course a totally new situation, with different individuals.

Also, Torres may spring to life at Chelsea; it wouldn’t surprise me. But with every passing month in this kind of form, the sense that his best is behind him will become stronger. Add the British record price tag – something that didn’t weigh him down at Anfield – and the fact that he appears to be forcibly shoe-horned into a formation that doesn’t suit the team (and therefore him), and it becomes even harder for him to be the sensation we witnessed between 2007 and 2009.

(Of course, there’s a chance that Chelsea may end up being successful even if Torres never returns to his sharpest; if he plays a role in them winning major honours, they’ll have few complaints.)

Style

One of fans’ key dislikes is hoofing from the back. Carroll represents a fear, in that he’s presents an easy option for the less cultured centre-backs to boot the ball long. So there might be occasions when he’s sought out at the wrong time, where a pass to someone else might be more wise.

However, the flip side is that when defenders are forced to clear their lines, they now have someone who can turn a clearance made under pressure into almost a 50-50 chance to keep possession.

I say 50-50, as centre-backs have an easier task winning headers because, usually, there’s two of them to one striker, and they aren’t looking to do anything bar clear the ball the way they are facing; even if the forward wins the header, if he flicks the ball beyond the centre-backs the likelihood is that the keeper will sweep up.

So normally, a striker has a less than 50-50 chance of winning the header – he’s outnumbered – and if he does win it, the chance of retaining possession – because there are more defenders and also a keeper looking to pick up the second ball – makes it around 20-80 at best.

Where Carroll excels is that: a) he’s big and strong, b) he has a great leap, and c) the accuracy of his headers (and chested lay-offs) is exceptional. We saw against Braga that possession could be built higher up the pitch, by Carroll winning it in those areas, in a way that Kuyt couldn’t.

Of course, this is essentially what Roy Hodgson wanted: bypass midfield, and have two big men to hold the ball up, and then the midfield join in. The trouble was, he had us play this way even when we clearly lacked the personnel; and it should be an option in a game, not Plans A-Z. The Liverpool way is not to try to pass from the back, first and foremost.

A further problem was that Hodgson appeared to want two strikers, playing parallel. Only last week, Steve McLaren noted how hard it is to play with a flat 4-4-2 these days, with two out-and-out strikers.

Hodgson seemed to realise this at Fulham, with Zoltan Gera in the hole, but at Liverpool – despite the option of Gerrard – he often opted for the flat pairing of Ngog and Torres. (You could see Hodgson buying Carroll, but not Suarez. And Carroll without that kind of partner is not something I’d be happy to see.)

When he came on against United, Carroll looked slow and clunky, as befits a big lad who’s spent months on the sidelines. It could be a while before the pace (of which he has a decent amount) and power return. There were signs against Braga, but he’s not yet at the level seen earlier in the season.

The rest of this campaign should be about acclimatisation. Even if he offers absolutely nothing this season, it can serve as a bedding-in process; the like of which would possibly have affected next season, if he had been bought this summer. By the time August comes, he should feel part of the furniture.